Justin Vivian Bond is named a recipient of a 2024 MacArthur Fellowship.

PROFILE

Mx Justin Vivian Bond has appeared on stage (Broadway and Off-Broadway, London’s West End), screen (Shortbus, Can You Ever Forgive Me?, Sunset Stories), television (High Maintenance, Difficult People, The Get Down), nightclub stages (most notably a decades-long residency at Joe’s Pub at The Public Theater in NYC), and in concert halls worldwide (Carnegie Hall, The Sydney Opera House).

Their visual art and installations have been seen in museums and galleries in the US (Participant, Inc, The New Museum) and abroad (Vitrine, London). Vivian’s artwork is also included in the permanent collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Their memoir Tango: My Childhood Backwards and in High Heels (Feminist Press) won the Lambda Literary Award for Transgender Nonfiction. They are the recipient of an Obie, a Bessie, and a Tony nomination, an Ethyl Eichelberger Award, The Peter Reed Foundation Grant, The Foundation for Contemporary Art Grant for Artists, and The Art Matters Grant. In 2024, Justin Vivian Bond was named a recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship. In 2025, Bard College will award them an Honorary Doctorate of the Arts.

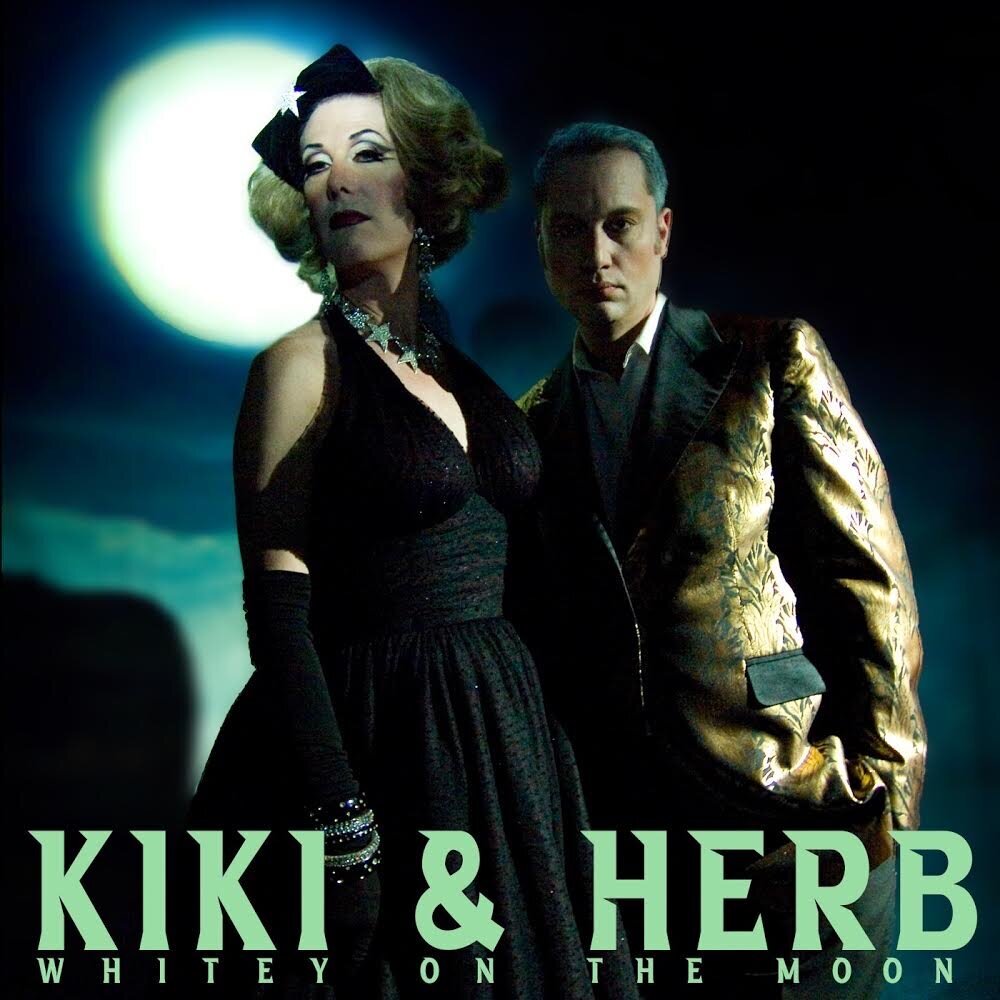

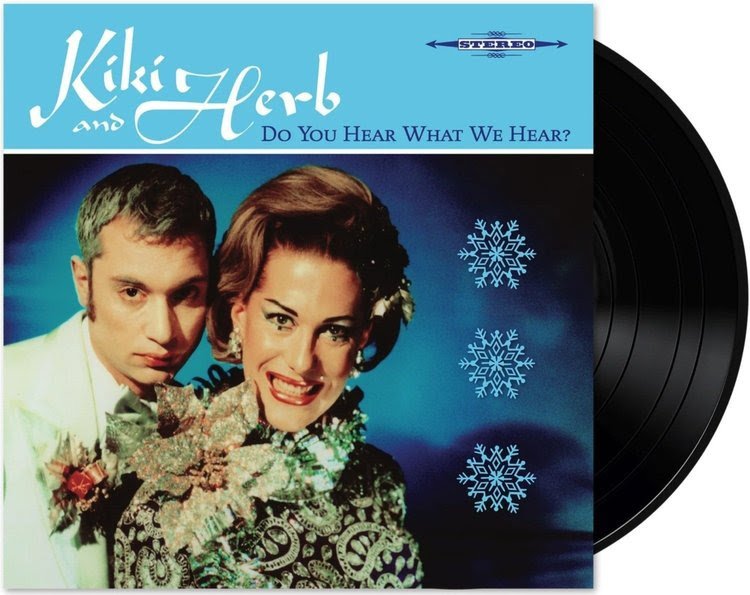

They have self-released several full-length recordings: most notably Dendrophile and Silver Wells. In 2022, they released Only an Octave Apart (Decca Records), a critically acclaimed collaboration with Anthony Roth Costanzo, produced by Thomas Bartlett with arrangements by Nico Muhly. As one half of the legendary punk cabaret duo Kiki & Herb, they toured the world and released two CDs: Do You Hear What We Hear? and Kiki and Herb Will Die For You at Carnegie Hall.

Mx Bond has been at the forefront of Trans visibility and activism since the early 1990s. They won an Audie Award for Best Non-Fiction narration for the audiobook Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar, the National Book Critics Circle Award-winning biography by C. Carr. They have a Master’s Degree in Performance Design from Central Saint Martins College in London and have taught performance composition and Live Art Installation at NYU and Bard College. Currently, Viv divides their time between residences in New York City’s East Village and the Hudson Valley. In December 2019, they made their debut at The Vienna Staatsoper in the world premiere of Olga Neuwirth’s Orlando as Orlando’s child.

In 2025 Vivian is scheduled to appear in Complications in Sue, a new opera commissioned by Opera Philadelphia conceived by Viv with a libretto by the Tony Award-winning writer Michael R. Jackson.

UPCOMING SHOW: JOE’S PUB

MAY 6 - MAY 11, 2025

at Joe’s Pub at The Public Theater

Following on the sensible heels of last fall’s Radclyffe Hall inspired sold-out-sapphic/song-cycle, Oh, Well, Justin Vivian Bond and and band continue into spring with Well, Well another outing highlighting songs by our great lesbian, trans singer, and gender non-conforming songwriters.

Featuring songs from St. Vincent, Sophie, Janis Ian, Billie Eilish, and Benjamin Smoke Viv has a flick through multiple decades of dyke drama and transeuphoria.

Once again Viv is here to prove THERE’S NO CABARET WITHOUT THE T!

With:

Matt Ray, M.D and piano

Bernice “Boom Boom” Brooks, drums

Nathann Carrera, guitar

Claudia Chopek, violin

Mike Jackson, bass

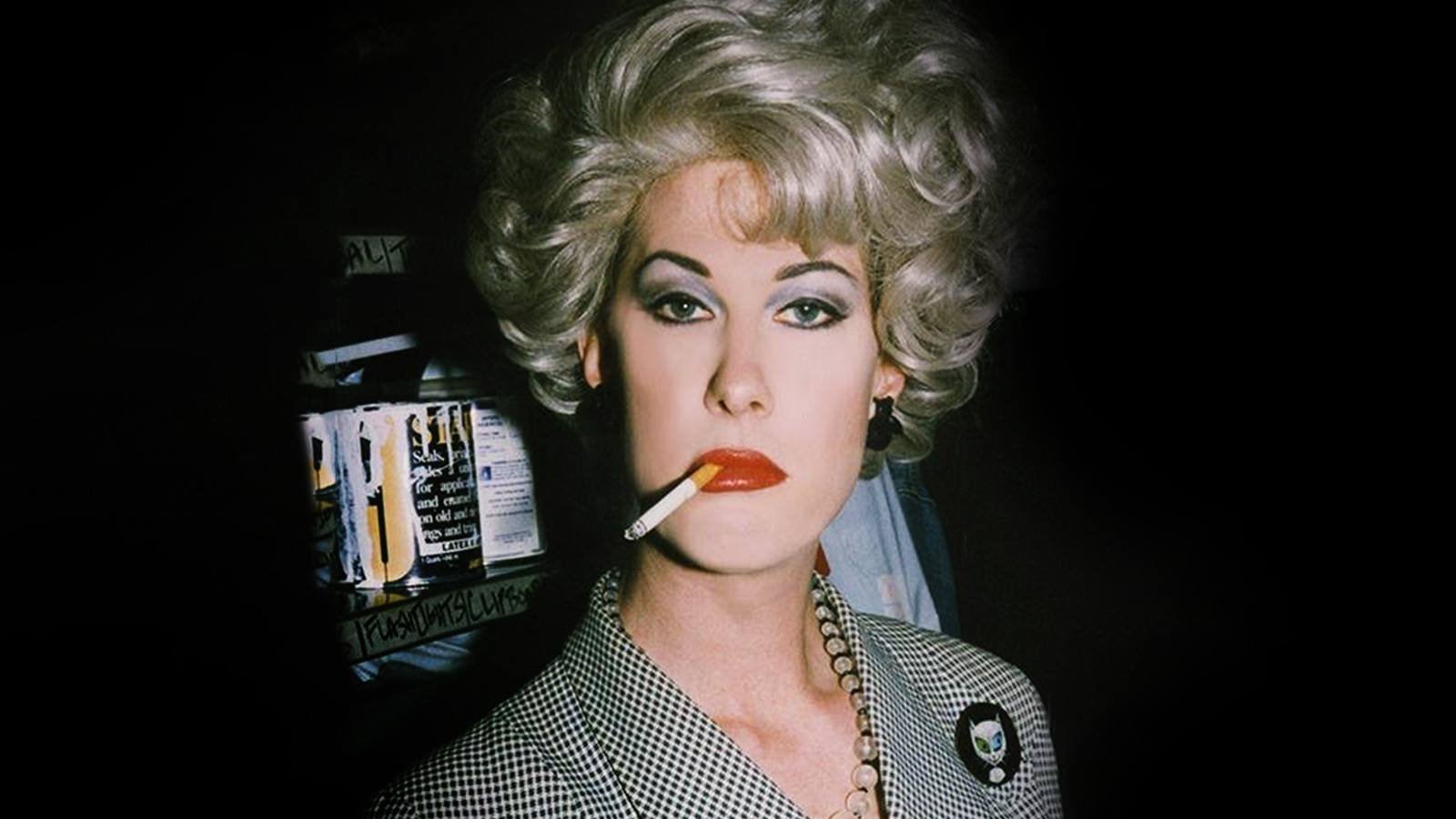

Photo Credit: Greg Gorman for LA Eyeworks

It makes the art better: A one-on-one with Mx Justin Vivian Bond, 2022.

While we at A.C.T. (American Conservatory Theater) are excited to hear the denizens of San Francisco sing their tales of the city again, we also acknowledge that the casting of a cisgender woman as a transgender character in our original production of Tales of the City, The Musical is an outdated practice that was harmful then, and is harmful now. A.C.T. takes representation on our stages seriously, and we want to use our platform to talk about how casting practices have evolved for the better since 2011.

We are making available for all this filmed conversation with Mx Justin Vivian Bond, who made history as the first actor who identifies as transgender to play a trans character on Broadway, and A.C.T. Artistic Director Pam MacKinnon, discussing highlights of Vivian’s career as well as the importance of trans representation and diversity in the industry.

Additionally, a portion of ticket sales for Tales of the City will be donated to The Transgender District and the Transgender-Variant & Intersex Justice Project (TGIJP). To learn more about these organizations, please visit transgenderdistrictsf.com and tgijp.org.

Spring 2021: “This look is from the Show-on-the-Wall, which happened during the pandemic,” says Jonathan Anderson. “I like that it’s incredibly bottom heavy. It could be a dress. It could be a ballgown. It could be a winter coat. I like how simplistic it was as a concept.”

Spring 2022 “Volume equals power,” Anderson says. “When you look at this tracksuit, when you see that blunt line against a gray landscape on a gray day, you’re not going to miss it. And I feel like, as in life, it’s better that you don’t miss it.”

Fall 2018 “This was from a show based on the architect E.W. Godwin, who was a brilliant designer for Oscar Wilde,” Anderson says. “It was a riff on a cape—there is something very operatic about it.”

Spring 2022 “With this most recent collection, I feel like I have started again at Loewe,” Anderson says. “It was one of the most nerve-racking shows I’ve ever done, and the most complex in terms of materiality and casting body shapes into silk and chiffon. It was also the biggest transformation of my own aesthetics. Ultimately, it was based around my all-time favorite painting: Pietro Perugino’s The Ascension of Christ.”

Spring 2016 “I thought this could be twisted by Viv in a 1940s Hollywood way, something with a nice kinetic movement.”

Fall 2019 “This was a turning point for me. The shapes became very reduced, very cartoonlike,” Anderson says. “I really love the bluntness of this coat. The previous shows were very eclectic, so this was a moment where we stripped things down to the knee, the leg, and thought about the coat as a kind of minidress.”

Spring 2022

Fall 2020 “I love the idea of a coat that is suspended. I was thinking about camp Hollywood glamour. At the moment, I’m quite into the idea of dressing in a way that is very The Day of the Locust—something abstract.”

New York Times Critic’s Pick Review:

Philip Glass and the Bangles, Mashed at the Symphony

Anthony Roth Costanzo and Justin Vivian Bond brought their gleeful opera-cabaret show “Only an Octave Apart” to the New York Philharmonic.

“It was sublime.

By turns hilarious and tender — those dual Didos are very much not played for laughs — the show was a small miracle of careful craft and improvisatory looseness, of arch personae and moving sincerity. Costanzo was a superb, well, straight man to Bond’s battiness, and their voices — one slender and pure, the other husky and vibrato-heavy — improbably blended. The return to live performance after a year and a half of lockdowns only increased the poignancy and delight of their obvious mutual love and respect. It was a confection that nourished.”

— Zachary Woolfe | The New York Times | January 28, 2022

Photo: Nina Westervelt for Vogue Magazine. September 20, 2021.

Anthony Roth Costanzo and Justin Vivian Bond: Tiny Desk (Home) Concert.

Witch Eyes, by Viv, to protect you from evil chodes, (2020).

Click here to learn more.

Olga Neuwirth’s new adaptation of Virginia Woolf’s gender-crossing novel is

the first work by a woman at the Vienna State Opera. (2019)

Anna Clementi, left, with Justin Vivian Bond, and Constance Hauman. Credit: Michael Pöhn/Wiener Staatsoper

Justin Vivian Bond, left, with Anna Clementi and Constance Hauman.Credit: Michael Pöhn/Wiener Staatsoper

The invention of Orlando’s child, the character played by Mx. Bond (who prefers that gender-neutral honorific), is a nod to the rising visibility of trans and gender nonconforming people, including in the opera world, as one consequence of the doors opened by Orlando.

— Ben Miller, The New York Times

BBC: Vienna opera house stages first opera by woman

THE GUARDIAN: After 150 years, Vienna opera house stages first opera by a woman

NYTIMES: A Female Composer Makes History With ‘Orlando’ in Vienna

Tilda and Vivian, Central Park, NYC.

À La Table De Christian Louboutin Avec Olivia Palmero Et Kanika Kapoor

02/07/2018

Christian Louboutin est un chausseur qui aime les femmes, et les femmes aiment Christian Louboutin. En témoigne la longue liste de noms (français et internationaux) ayant répondu présent à son invitation à venir découvrir cette semaine sa nouvelle collection de souliers de la collection printemps-été 2019. Dans les salons historiques et grandioses de l’Eléphant Paname, Natalia Vodianova, Olivia Palermo, la chanteuse indienne Kanika Kapoor et Elisa Sednaoui viennent découvrir la collection de chaussures richement décorées, le tout dans une scénographie tout en miroirs et effets visuels. Après le cocktail, tous se retrouvent dans l’un des grands halls de l’hôtel particulier de la rue Volney pour un dîner intimiste à la lueur de la bougie. Là, Kristin Scott Thomas, Kevin Mischel et Derek Blasberg se laissent envoûter par la prestation piano-voix sensuelle de l’artiste New-Yorkaise Justin Vivian Bond. Un pur moment de luxe, glamour et volupté.

Photos: Jean Picon

Justin Vivian Bond, "My Model | My Self: I’ll Stand by You, 2017. New Museum, New York. Wallpaper made in collaboration with George Venson of [Voutsa], pink dress by Frank Masandrea (1947–1988). Photo by Scott Rudd.

“It’s very important to me that this dress is worn on World AIDS Day,” Bond continued. “So many queer people throughout history have created the beautiful gowns that straight women wear, or the beautiful homes that very privileged white straight people live in. We create their luxuries and their beauty and their world that so many people aspire to, and yet we’re still somehow marginalized.”

— W MAGAZINE | Oct. 31, 2017

Justin Vivian Bond: “Almost Cut My Hair” at Joe’s Pub at the Public Theater, December 14, 2016.

LOVE IS CRAZY

Théâtre National de Chaillot

26 février 2014

Ni Mr ni Mme, le suffixe « Mx » conviendrait en revanche pour Justin Vivian Bond, qui a refusé de choisir son camp d’une façon aussi tranchée. « Personnellement, je n’ai jamais envisagé de me ranger d’un côté ou de l’autre. Pour moi prétendre être une femme serait aussi faux que la comédie que l’on me demande de jouer depuis longtemps, celle d’être un homme. J’aimerais avoir le luxe de la liberté de m’exprimer avec le plus d’honnêteté possible et de faire respecter ma vérité. […] Pour moi il n’existe pas de sexe opposé. Il n’y a que l’identité et le désir ».

-

Publié dans

Le blog d'Isatagada

La musique rend heureux

26 février 2014Mx Bond (que l’on peut aussi appeler V – « car Vivian commence par un V et que visuellement, un V est composé de deux côtés qui se rejoignent au milieu. »), outre ses talents de performer, chante, écrit, et peint. Après Kiki and Herb, Justin Vivian doit principalement sa notoriété au film de John Cameron Shortbus, sorti en novembre 2006 et qui le met en scène dans son propre rôle pour un final crescendo autant qu’inoubliable.

En ce lendemain de Saint Valentin, la légende du cabaret new-yorkais faisait au Théatre National de Chaillot l’une de ses rares apparitions parisiennes, en clôture de la série de représentations de Kabaret Warszawski. Au beau milieu du foyer, entouré d’un public d’afficionados attablés autour de verres de bon vin ou de coupes de champagnes (qu’on ne vous servira pas s’il n’est pas assez frais), l’ambiance n’a jamais été aussi « cabaret ».

L’entrée de l’artiste est triomphale. Les cheveux long blond platine, revêtue d’une robe longue fendue qui laisse deviner des jambes d’une finesse à faire pâlir d’envie n’importe quelle femme (trop) normalement constituée, parée d’escarpins aux talons argent vertigineux (« They ARE Chanel »), Justin Vivian Bond est là pour faire le show.

Saluée par la pleine lune comme par la Tour Eiffel, accompagnée d’un trio guitare piano et violon, l’américaine livre un récital dont l’Hexagone reste assez peu coutumier, mêlant humour et chansons, se distinguant par dessus tout par ses longs monologues – souvent hilarants.Rapidement, l’image « trans-genre » s’efface pour laisser place à une personnalité hors normes attachante et assez fascinante. Sur scène on se laisse prendre totalement par le spectacle, sans plus chercher à qui l’on a affaire tellement la question parait finalement peu essentielle.

A la fois drôle et émouvante, forte d’une voix qui ne joue aucun autre rôle que le sien, le charisme de Mx Bond écrase tout le reste.

Love is Crazy lui donne l’occasion de chanter ses chansons préférées, dont un extraordinaire (dans le sens premier du terme) In The End repris en cœur par la salle toute entière tandis que l’artiste mime des cuivres grandioses avant de se lancer dans un délire sur les défibrillateurs portables.

A ce compte, les ovations et rappels seront à la hauteur d’une soirée d’exception.

NDLR : l’utilisation du féminin ou du masculin alterne, totalement au feeling.

-

Published In

Le blog d'Isatagada

La musique rend heureux

February 26, 2014Neither Mr. nor Ms., the title “Mx” is much more fitting for Justin Vivian Bond, who has refused to pick a side in such a binary way.

“Personally, I’ve never considered aligning myself with one side or the other. For me, pretending to be a woman would be just as false as the performance I’ve been asked to give for so long—that of being a man. I want the luxury of the freedom to express myself as honestly as possible and to have my truth respected. […] To me, there’s no such thing as the opposite sex. There is only identity and desire.”

Mx Bond (also known as V—"because Vivian starts with a V, and visually, a V is made of two sides that meet in the middle"), in addition to being a talented performer, sings, writes, and paints. After Kiki and Herb, Justin Vivian is best known for starring as themselves in John Cameron Mitchell’s film Shortbus, released in November 2006, where they appear in the final, unforgettable crescendo scene.

The day after Valentine’s Day, the New York cabaret legend made one of their rare Paris appearances at the Théâtre National de Chaillot, closing out the run of Kabaret Warszawski. Right in the middle of the venue’s lobby, surrounded by a devoted audience seated at tables with glasses of good wine or champagne flutes (which, by the way, won’t be served if not properly chilled), the atmosphere couldn’t have been more “cabaret.”

The artist’s entrance is nothing short of triumphant. Long platinum blonde hair, wearing a floor-length gown with a high slit revealing legs that could make any (overly) conventionally built woman green with envy, and towering silver Chanel heels (“They ARE Chanel”), Justin Vivian Bond is here to put on a show.

Bathed in moonlight and framed by the Eiffel Tower, backed by a trio on guitar, piano, and violin, the American performer delivers a type of recital that’s still quite rare in France—a blend of humor and song, with standout moments coming from long, often hilarious monologues.

Before long, the "trans-genre" image fades away, making room for a singular, captivating personality. On stage, the performance is so absorbing that questions about identity melt away—they just don’t seem to matter anymore.

Both funny and deeply moving, with a voice that isn’t pretending to be anything but itself, Mx. Bond’s charisma eclipses everything else.

Love is Crazy gives them a chance to perform favorite songs, including an extraordinary (in the truest sense of the word) rendition of In The End, taken up by the entire audience in a communal chorus while the artist mimics grandiose brass instruments before launching into a wild riff about portable defibrillators.

And just like that, the standing ovations and curtain calls live up to what was truly a one-of-a-kind evening.

Editor’s Note: The use of feminine or masculine pronouns varies throughout, entirely based on instinct.

Tim Murphy:

You have a new CD out in March called “Justin Vivian Bond: Dendrophile.” Explain.

Vivian:

A dendrophile’s a person who gets an erotic charge out of nature. I am one! This is a record for the tree-hugger community. I do Bambi Lake’s “The Golden Age of Hustlers” on it, and also a duet of the Carpenters’ “Superstar” with Beth Orton. As for Vivian, that’s my self-given middle name. Justin is a very male-identified name, and I wanted something that would balance it. I had an uncle named Vivian Francis. He was a wonderful person, but he changed his name to Victor. He didn’t like being Vivian. But it’s fine with me.

— New York Times, December 7, 2010

“Golden Age of Hustlers” from the album “Dendrophile”. Performer: Justin Vivian Bond Song by: Bambi Lake Co-Directors: Silas Howard & Erin Greenwell Producer: Ethan Weinstock Cinematographer: PJ raval Editor: Janis Vogel "The Golden Age of Hustlers" captures the 1970's gay hustler scenes of pre-HIV/AIDS era on Polk St in San Francisco from an insider's experience. 2014.

Justin Vivian Bond, with Nath-Ann Carrera on guitar, performs the song "The New Economy" from the album “Dendrophile” from a Lower East Side rooftop, 2011.

I'm thrilled to be debuting the first video for Dendrophile. Its called American Wedding and the lyrics are by Essex Hemphill. It's the first song on the recording and I consider it to be an invocation.“American Wedding from the album “Dendrophile”. 2011.

KABARET WARZAWSKI (2013)

Stage Direction Krzysztof Warlikowski

Inspired by I Am a Camera by John van Druten, Les Bienveillantes by Jonathan Littell, Shortbus by John Cameron Mitchell and Tango by Justin Vivian Bond

Adaptation by Krzysztof Warlikowski, Piotr Gruszczyński, Szczepan Orłowski

-

The two distinct historical realities channeled here – Weimar Germany prior to the Nazi takeover, and post-9/11 New York – are virtual laboratories of time and space, in which historical circumstances bring out hidden and repressed fears, as well as sexual and erotic phobias and longing that cause tension and lead to all sorts of crisis situations.

These two worlds serve as a mirror in which the Warsaw of today can see itself. In bringing together these two eras and places, the director explores the limits or restrictions on freedom in today’s world. In an age of uniformity and oppressive normalization, imposed partly in the name of collective security, people’s right to be themselves and their freedom of self-expression are increasingly curtailed and undermined. Consequently, societal norms are becoming a prison of sorts. These restrictions can only be circumvented in closed, all-but-underground spaces to which only insiders are admitted. Theatre is one such space. With this production, Warlikowski, notorious for engaging his spectators in an unending debate about the issues that matter most, has chosen to work within the genre of cabaret, whose basic assumptions include addressing spectators directly and breaking the convention of the fourth wall separating performers from their audience. Cabaret is by definition a space of freedom, governed by the misrule of a never-ending carnival.

With Kabaret warszawski, the team of Nowy Teatr confronts diverse scenarios of oppression. The play portrays a group of artists who exist for the sake of art. But art proves fatal for its acolytes, infusing them with doubt and making life impossible. In creating a therapeutic space where fears and taboos can be Warlikowski shows the threats and oppression that inevitably accrue around such enclaves.

-

Written by Bryce Lease for

The Theatre Times

Published 17th Oct 2016

Essay, LGBTQ+ Theatre, PolandIn Poland, the emergence of a public dialogue on alternative sexuality was first and foremost framed by conservative anti-homosexual attitudes that found their legitimation in Catholic doctrine. Terminology such as ‘closet’, ‘coming out’ and ‘homophobia’ only arrived belatedly around 1998. Against this background, Polish theatre director Krzysztof Warlikowski has had a profound impact on the representation of alternative sexualities across the political spectrum, from accepted coming-out narratives and gay emancipation in his 2007 production of Tony Kushner’s Angels in America (Anioły w Ameryce) to the construction of queer counternarratives that depicted alternative structures of kinship and forms of intimacy in his original adaptation Kabaret Warszawski (Warsaw Cabaret, 2013). Charting the movement between Warlikowski’s two productions, both of which superimpose New York City on top of contemporary Warsaw, will allow me to draw attention to a wider recent shift in cultural focus from gay rights to queer counterpublics.

Warlikowski’s revolutionary staging of Kushner’s Angels in America directly attempted to rectify the lack of a concrete gay emancipatory movement in Poland. Warlikowski’s determining staging provoked a new public discourse around homosexuality that allowed for a crucial representational counterdiscourse to the Kaczyńskis’ neoconservative Fourth Republic. He also established a broadly identifiable historical shift in the treatment and perception of homosexuality and HIV/AIDS that was in sympathetic dialogue with, and later considered a significant component of, the ‘rainbow revolution’– a manifestation of Polish gays and lesbians who protested against conservative Catholic groups and the loss of privileges granted to citizens across virtually the rest of Europe. Superimposing the New York of the 1980s over Warsaw at the turn of the millennium, Kushner’s attack on Ronald Reagan functioned as a stand-in for Warlikowski’s caustic critique of the Kaczyńskis’ blatant opposition to liberal pluralism and their own particular brand of neoconservatism that combined notions of cultural exclusivity and superiority with Christian values and a championing of the free market. Angels in America gave explicit form to a possibility of a theatre that did not attempt to universalise specifically gay identities but focused on their visibility as an expression of their particularity.

Warlikowski expertly collided black humour with irony, fantasy, and absurdism in his critique of modern sexual relationships. Angels in America owed a great deal of its force to the score composed by Adam Falkiewicz. The sound, reminiscent of Antony Hegarty, was described as ‘shy, fearful, in hiding’ (Cyz, 2008), reflecting the anxiety of full disclosure experienced by the closeted characters. Roy Cohn, the infamous lawyer responsible for the execution of Ethel Rosenberg, for example, refuses to identify himself as homosexual. Cohn sees himself as a heterosexual who happens to have sex with men. Cohn is a mentor to Joe Pitt, a young Mormon lawyer who in one climactic scene phones his mother in Utah in the middle of the night to reveal his sexual orientation. Until this point, the word gay is never mentioned. Reviewers were preoccupied with this coming-out scene not only for the precision of the acting skill displayed by Maciej Stuhr (Joe Pitt) but also for the admittedly troubling connection insinuated between American Mormons and Polish Catholics. Jacek Poniedziałek, who played Louis Ironson, and also translated the play into Polish, corroborated this correlation, claiming that Kushner’s representation of Mormons obsessed by the Ten Commandments was similar to the radically-minded listeners of the ultra-conservative Radio Maryja (St. Mary’s Radio).

Angels in America also confronted the absence of a public discourse on HIV/AIDS in Poland. The first recorded performance to deal with the subject, as late as 2005, was Maciej Kowalewski’s Miss HIV, based on a real-life beauty contest held annually in Gaborone, Botswana. In the play the contest, in which all the participants are living with the virus, is supported by the country’s government in an effort to promote tolerance and reduce the stigma attached to HIV. Significantly, the five contenders of various ages and social classes were heterosexual women, thus challenging the received perception of HIV as a disease exclusively contracted by homosexuals and drug addicts. Kowalewski used HIV as a conceptual tool to comment on the media’s hypocritical treatment of illness in general, exploiting subjects it purports to bring to light, sponsor or protect. For Warlikowski, HIV/AIDS was an important lens through which to critique nationalism. Despite many reviewers’ focus on themes such as forgiveness, tolerance and compassion in Angels in America, the director was adamant that the crucial problem in the play was the depiction of a healthy lover living with an AIDS patient. When Prior Walter appears in a stupor at the end of Millennium Approaches wearing a crown of thorns and a purple robe this directly engaged the image of Christ’s Passion for Polish audiences. Cultural commentator Rafał Węgrzyniak (2009) has argued that the Passion is virtually absent in the work of the younger generation of Polish directors, likely the result of widespread progressive secularization and the ongoing culture war between conservative Catholics and progressive liberals. Warlikowski troubled the legacy of artists as transmuters of Polish Romanticism and threatened the conjunction of national identity with heterosexually-bounded Catholicism. By making the disease the enemy around which Poles could rally, Warlikowski complicated a tendency that implicitly participates in the idealization of heteronormative and nationalist exclusionary identity formation.

Warlikowski suggested that, amidst the changes occurring in the country, Warsaw increasingly became a forum for rebels and queers in Poland. Certain reviewers were convinced that Warlikowski’s mapping of New York onto Warsaw made for a convincing coupling. Others were only perfunctorily interested in this geographical and temporal conjunction. There is no question that Warlikowski’s performance provisions a visual vocabulary actively shaping language and ways of thinking about the world that – while not being hostile towards – are not necessarily in accordance with the politics of Kushner’s authorial agenda. Though somewhat irritated by the camp or sickly sentimental Americanisms, they paid more attention to the play’s interculturally transposable themes. There were, however, other conflicts between the American and Polish contexts. Kushner categorically condemns Ronald Reagan, who is valourised in Poland as ‘the slayer of communism and champion of free markets,’ and there is a barely concealed overlap between Reagan and Lech Kaczyński in this adaptation. In an attempt to make the cultural crossover more evident, a television positioned at the front of the stage showed news from Warsaw cut with panoramic views of New York City. Fictional and authentic news stories were interspersed, their conjunction articulating the world that is not entirely conditioned by the local Polish contexts or globalised American politics.

Queer publics

Warlikowski’s next major production to deal with queer identities and the cultivation of an oppositional consciousness was Kabaret Warszawski (2013). If Angels in America foregrounded the visibility of gay men within a clearly defined coming-out narrative, Kabaret Warszawski offered a critique of identity politics that rejects minoritising concepts of the subject by eschewing singular sexual identities (gay) in favour of anti-identitarian energies (queer). Angels was also Warlikowski’s last attempt to stage a single text: two moments of artistic force spawning from heightened political tension are contrasted: the dissolution of the Weimar Republic in Berlin and the aftermath of 9/11 in New York City. The juxtaposition between these cities and historical moments revealed existing phobias in contemporary Warsaw. The first half of the performance was a revision of John van Druten’s 1951 play I am Camera based on Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Stories, germane in its associations with the recent resurgence of neo-fascism in Central and East Europe, while the second part adapted John Cameron Mitchell’s 2006 Shortbus, a film that depicts a group of New Yorkers who meet weekly in a utopic salon where sexually diverse practices and normally controlled libidinous desires can be freely enacted. The impetus for this production resulted from a growing wave of aggression Warlikowski and his ensemble recognised in the extreme right in Poland. Influenced by Polish artist Artur Zmijewski’s video installation Democracies (2007-12), a series of thirty short films which document various manifestations of political activity in public space such as protests, rallies and parades in which anti-Semitic and homophobic feelings erupt on a mass scale, Warlikowski’s project mirrors Zmijewski’s belief that culture is a dialectical field for political thought and action rather than a stable set of moral values and traditions.

Using conventions of cabaret allowed Warlikowski and his ensemble to break the fourth wall and engage the carnivalesque as a means of providing a space for self-determination that promoted personal contact with the audience. Beyond simple good-humoured fun, appropriating the specific form of cabaret from Weimar Berlin was a productive tool to embody scathing anti-normative critiques of ultra-rightwing movements that merged art with power, magnifying new forms of extremism and their means of justification. Warlikowski merged the Nazi dictatorship with the American dream and the mass commodification of culture through projected images of the opening ceremony of the 1936 Berlin Olympics, which revealed participation and implicit collusion on an international level as many teams performed the Hitlergruß, the infamous Nazi salute. Fascism and globalised consumerism were again paired in the emblem of the swastika, which was inscribed on costumes of the cabaret dancers in the bright red and blue colours that form the Pepsi-Cola logo.

In Sally Bowles’ raucous song and dance routines, Christopher, van Duten’s protagonist based on Christopher Isherwood, succumbs to an authoritarian father figure, symbolized by a buffoonish Hitler, who is himself an elated spectator at the cabaret. This depiction of Hitler reflects feminist Agnieszka Graff’s warning that economic stagnation in Poland has produced a crisis of masculinity, a generation of young men frustrated with the democratic system who are targets for non-democratic slogans. The reinforcement of masculine heroism in Poland in the twentieth century was understood as the only mode in which to build horizontal trust amongst young men in the ongoing struggles against occupying forces. Graff argues that this process of engagement today is radicalising young men to the far right, which is resulting in the increase of a fascistic climate. Subverting the typical portrayal of Hitler as a menacing or forbidding personage in exchange for a lighthearted and friendly father figure with strong, but down-to-earth views made his current appeal plausible. Moreover, the performance style of cabaret places primary significance on sexuality, presenting bodies on stage that undermine gender cohesion and amplify popular homophobic and misogynistic beliefs through humour and parody. The repetition of Hitler’s clownish gestures provided a critical distance that revealed the perverse underlying temptation for an embattled straight white masculinity. The fact that Hitler takes pleasure from watching the cabaret that mocks him only further illustrates the elasticity of contemporary liberal democracy in accommodating such neo-fascistic positions.

Warlikowski has commented that there are no longer homosexual themes and ‘gay’ characters in his work, but rather performative attempts to subvert hegemonic culture. Jacek Poniedziałek’s performance as Justin Vivian Bond, the New York-based transgendered performance artist, strategically enacted a trans identity that continues to be even more taboo than homosexuality in Poland. Bond is a member of the Radical Faerie movement, a countercultural network that embraces new-age spirituality and promotes queer paradigms beyond hetero-imitation. In Kabaret, Bond’s appearance is reminiscent of Ariel in Warlikowski’s 2003 Tempest – an impish and erotically charged presence that breaks strong cultural norms. The multivalent erotic energies in the adaptation of Shortbus signal the absence of a sexual revolution in Poland, which has made it difficult to establish alternatives in public discourse outside of the nuclear family fetishised by the Church. Warlikowski continued this deconstruction of the standard heterosexual nuclear family in Kabaret. The physical relationship established with the audience through eye contact and physical touch, the sharing at one point of a marijuana joint and a concurrent use of the audience seating area as performance space created a mutual co-presence between performer and spectator that was affecting, temporal and inclusive. It is fair to argue that Warlikowski’s explorations of cultural alterity have established a new category of an audience in Poland.

European Tour Archive:

3–6 July 2013, Gdynia, Poland, Festiwal Open’er

19–25 July 2013, Avignon, France, Festival d’Avignon

16–17 October 2013, Wrocław, Poland, Międzynarodowy Festiwal Teatralny Dialog

14–15 December 2013, Kraków, Poland, Międzynarodowy Festiwal Teatralny Boska Komedia

7–14 February 2014, Paris, France, Théâtre National de Chaillot

6–7 March 2014, Luxembourg City, Luxembourg, Les Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg

13–15 March 2014, Liège, Belgium, Le Théâtre de la Place

3–4 April 2014, Clermont-Ferrand, France, La Comédie de Clermont-Ferrand

24–26 June 2014, Munich, Germany, Munich Opera Festival

10–11 October 2016, Vilnius, Lithuania, Festiwal Sirenos

Bond's theatrical streak reshapes itself on this collection: the songs form a parallel narrative to Joan Didion's novel Play It As It Lays, tapping into its themes of isolation and grim self-reliance through songs by tough storytellers like Mark Eitzel, Leonard Cohen and Joni Mitchell. Thomas "Doveman" Bartlett's piano arrangements support Bond's intense soliloquys.

— Ann Powers | NPR Music | June 15, 2012

Justin Vivian Bond ("Kiki & Herb: Alive on Broadway") prepared to perform "Silver Wells" at 54 Below, in celebration of the album of the same name. Here, Bond performed "Stars" and spoke to Playbill about some of the other songs in the concert, 2014.

“Patriot’s Heart” from the album “Silver Wells” at Le Poisson Rouge, NYC, 2012.

TANGO: MY CHILDHOOD, BACKWARDS AND IN HIGH HEELS

Bond recalls in vivid detail how it looked and felt to first discover Mom's lipstick (Iced Watermelon by Revlon). Growing up haunted by their awareness of being “different,” Bond began to foster intimate friendships with girls, and to feel increasingly at risk with boys. But when the bully next door wanted to meet in secret, Bond couldn't resist. Their trysts went on for years, making Bond acutely aware of how sexual power and vulnerability can intertwine. With inimitable style, Bond raises issues about LBGTQ adolescence, parenting trans/queer children, and bullying, all while being utterly entertaining.

"Tango is a raw nerve touching an electric soul, a beautiful book, written with honesty, pain, and joy from one of our great modern day shamans."

—Sandra Bernhard

“Justin Bond has written a very important book for all of us to read.

Thank you, Justin, for your courage in writing the truth of what you went through as a transgender child in this society. Thank you, also, for your sense of humor. It made the book fun to read as well.”

—Yoko Ono

"Tango should be in the hands of every child who can read, and of every adult who cares about that child."

—Michael Warner, professor of English at Yale University

“Bond’s fabulosity is matched by a trenchant wit, and [V’s] over-the-top stories are smartly edged with politics, sexual or otherwise.”

—New York Times

"Reading Tango is like listening to your favorite eccentric cousin or auntie tell you hair-dressing tales of innocence lost and found, friendships forged of adversity, and bullies bewildered by their own perversity. Justin Vivian spins a one-of-a-kind story that you won't be able to put down."

—Kate Bornstein, author of Gender Outlaw

"When I say Justin Vivian is a true original, what I mean is, Justin doesn't resemble anyone else on the face of the planet. When I say Justin Vivian Bond is touched by genius, I mean exactly that."

—Michael Cunningham, author of The Hours

"Justin Vivian Bond is a lighting rod, a solid steel structure hin heels that attracts burning chaos and disciplines it into orderly submission. Am I allowed to say that Justin is a God?"

—Rufus Wainwright

PURCHASE AT YOUR LOCAL BOOKSTORE →

AUDIOBOOK NARRATED BY VIVIAN →

Available as an ebook on:

Kindle

Nook

Apple iBooks

Kobo

Justin Bond, at Joe’s Pub, is a gender-bending, truth-telling illusionist.Illustration by ROBERT RISKO

-

It is said of many show-business legends that they lose touch with the ordinary world and become cartoons of their former selves. The opulently dissipated Kiki DuRane—a sixty-something lounge singer who tours ad nauseam with a doleful accompanist named Herb—has gone in the opposite direction; she is a fictional creation who has acquired the grit and the glow of the real. Kiki and Herb are the invention of the writer-performer Justin Bond and the pianist Kenny Mellman, who have long been fixtures at downtown New York venues like Flamingo East, P.S. 122, and Fez. They have refined their act into an Off Broadway show, “Kiki & Herb: Coup de Théâtre,” which recently opened at the Cherry Lane. It is a slashingly funny, psychically unsettling entertainment—part cabaret, part rock and roll, part Victorian melodrama—to which the category of camp does not apply. Camp implies knowingness and detachment; Bond’s Kiki is anarchic and atavistic, in the grip of forces beyond her control. She is almost militant in her decrepitude. Reminiscing airily about her old friend Grace Kelly, barking obscenely at childhood foes, drifting into a sullen stupor, snapping back to life with yawps of vicious glee, Kiki is a beacon of insanity in a world that may finally be coming around to her point of view.

The conceit of the show is that Kiki, a self-described “boozy chanteusie,” is aiming to attract new listeners by singing contemporary hits. “It is both thrilling and humbling that so many young people have, as it were, ‘tuned in to our sound,’ ” she says, with the overenunciation of the early-evening alcoholic. Thus begins a scorched-earth advance across decades of pop music, from Bob Merrill’s “Make Yourself Comfortable” to Kylie Minogue’s “Can’t Get You Out of My Head.” Kiki’s wild stabs at modern trends recall such classic miscalculations as Mae West’s renditions of Beatles songs and Ethel Merman’s disco album, but the genius of Kiki is that her entire career seems to consist of bungled crossover projects: a bossa-nova album (“Kiki and Herb: Don’t Blame It on Kiki and Herb,” 1964); a spoken-word record (“Kiki and Herb: Whitey on the Moon,” 1972); a belated disco effort (“Kiki and Herb: One Last Chance to Blow,” 1983). The songstress hurls herself at this material with such dire enthusiasm that she takes full possession of it. Lately, she has taken an interest in rap, which she calls “the folk music of today.” In past shows, she has sung Wu-Tang Clan and Snoop Doggy Dogg, adding jazz vocalise to such lyrics as “All my niggaz and my bitches / Throw your motherfuckin’ hands in the air!” This time, she takes on Eminem, whose self-pitying hysteria suits her beautifully.

Between the songs come autobiographical vignettes. Bond has mapped out the life of Kiki in loving detail, and each show adds a few new twists to the familiar downward spiral. The singer was born during the Great Depression, overshadowed by tragedy from the start. “A lot of people jumped out of windows when the stock market collapsed in 1929,” she recalls, “but not all of them died. My father was such a man.” She was given the diagnosis of “retard” and placed in a children’s institution in western Pennsylvania. There she met Herb, a foundling of indeterminate origin. When Herb fell victim to a predatory delinquent named Danny, Kiki was there to comfort him, and a great friendship was born. (The Danny episode inspires one of the show’s set pieces, a dramatic monologue built around the song “I’m Ugly and I Don’t Know Why,” by an obscure band called Butt Trumpet, with adornments from the inspirational Christian poem “Footprints.”) The duo’s musical career developed only in fits and starts. There was a prolonged interruption when Kiki had to serve a jail sentence for the attempted murder of her first husband, an abusive boxer named Ruby. “I wasn’t trying to kill him,” Kiki explains, “only trying to get his attention.”

Throughout the evening, the chanteuse looks back wistfully to the year 1967, when her life turned momentarily grand. A flashback sequence re-creates the scene: Kiki and Herb are playing at the Grand Casino, in Monte Carlo, at the invitation of Princess Grace. They are making what should have been their triumphant comeback album, “Kiki and Herb: It’s Not Unusual.” Kiki has Aristotle Onassis as a lover, Maria Callas as a rival. Fortune has raised her up, but now a terrible tragedy lays her low. During a Mediterranean cruise, she leaves her seven-year-old daughter, Coco, alone on deck while she goes below to satisfy her carnal needs. “Ladies and gentlemen,” she says, head cast down, “where the hell can a kid go on the deck of a boat?” At this juncture, the performance begins to waver between black comedy and something like genuine pathos. Kiki’s failures as a singer pale next to her failures as a mother. The watery death of Coco haunts her. She has lost touch with her two other children, who claim not to know her, even though she sends them all her press clippings. She takes refuge in another glass of Canadian Club and ginger ale—the piano is equipped with a drink holder—and the drink begins to take its toll. She digresses, and digresses again—“Where was I, ladeezh n genlmn?”—and then stops, staring fixedly at nothing.

Just when it seems that the comic spirit of the evening has been swallowed up in melancholy, the original, rampaging Kiki returns, her extreme jazz vocals now fuelled by rage at herself and the world. She turns for solace to her fans, who have always stood by her side, albeit in dwindling numbers. What the world needs, she says, is more love, for “without love . . . there is only rape.” “

“Kiki & Herb” is a comedy, at least on the surface, but the performers are serious people who have managed to smuggle into their act a fair degree of theatrical and musical sophistication. Bond, who is forty, is a native of Hagers-town, Maryland. He studied classical acting in London, but he developed a distaste for that aspect of theatre which involved working with directors. He moved to San Francisco in 1988 and threw himself into street theatre, avant-garde noise, and conceptual cabaret. One night, while trying to think of an innovative birthday present for a friend, he drew age marks on his face and assumed the Kiki persona. He is resigned to being labelled a “drag queen,” although, after meeting him offstage, you want to find a mellower label for his particular brand of gender vagueness. Bond is simply a svelte person who looks stylish in women’s clothes, especially swinging-sixties outfits, like the ones that Faye Dunaway wore in “The Thomas Crown Affair.”

Mellman, who is thirty-four, has the innocent face, diffident air, and slightly bewildered expression of someone who has spent long hours at the piano since childhood. He studied composition at the University of California at Berkeley, but became disenchanted with the music department when he was told that Erik Satie’s seldom heard “Socrate” was too boring to warrant a performance. He switched to San Francisco State to study poetry, and sought a new medium for his musical curiosity. He found it when he met Bond, and began accompanying the singer in such hard-to-reconstruct night-club evenings as “Dixie McCall’s Patterns for Living.” Kiki barged to the forefront one night in 1993, when, at the end of a Gay Pride weekend, Bond and Mellman felt too exhausted to do their usual program. “You’re Herb, I’m Kiki,” Bond said, before they went onstage, and a fading star was born.

The early Kiki and Herb shows were more chaotic than the one now running at the Cherry Lane. They were fuelled by the energy and rage of aids activism—the in-your-face tactics of act up and Queer Nation. Bond and Mellman used to heighten the naturalism of the show by getting exactly as drunk onstage as the scenario demanded. When I first saw them, five years ago, Kiki would climb on top of café tables and order the customers to lick her legs. If you tried to move your drink out of the way, she might grab it out of your hand. Another night, she threw a tray of steak knives, fortunately causing no harm. When Bond was asked to perform at Madonna’s birthday party, he got into a scuffle with the R. & B. artist D’Angelo. Kiki and Herb emerged as much from the spit-spewing, scenery-chewing mentality of punk rock as from the cabaret tradition. It’s not much of a contradiction, when you consider how many of the original New York punk rockers came out of the avant-garde art scene, the gay underground, and other bohemias.

In the end, “Kiki & Herb” is a more political show than its premise suggests. We should really have expected no less from a woman who alleges to have been engaged to the radical black Presidential candidate Dick Gregory. The politics emerges not just in Kiki’s commentary on current affairs—summing up George W. Bush’s approach to homeland security, she advises, “Whatever you do, don’t go out and don’t stay in”—but also in her obsession with the figure of the abandoned, abused, or socially outcast child. The stories return relentlessly to this theme—a young gay boy raped by his classmates, a girl cast aside by her mother and placed in an institution. Of course, whenever Kiki is beginning to break your heart with these tales, she has to blurt out something stunningly grotesque. “If you weren’t abused as a child,” she declares, “you must have been an ugly kid.” The unshockable downtown crowd never fails to gasp at that one.

Only an academic paper in gender studies could do justice to the complexities of Kikiness. (In fact, an N.Y.U. graduate student has written a thesis on the subject.) The show also makes interesting points about music—about how songs are sung and about what they mean. This is where poor Herb comes to the fore. Kenny Mellman’s job is to make sense on the piano of his partner’s bizarre repertoire, and those who feel that modern pop songs have too much technology and too little music will enjoy his Luddite solutions. Rachmaninovian bass octaves give symphonic majesty to a song like Radiohead’s “Exit Music (for a Film).” To mimic the saturated textures of hip-hop production, he attacks the instrument in a dissonant, Cecil Taylor frenzy, substituting cluster chords for synthetic beats. He gets a huge, bellowing sound out of the piano. Herb, as Kiki portrays him, is a damaged child seeking refuge in music, and the piano is the vehicle of his revenge.

The high points of the show are the medleys, which are carefully constructed simulations of music losing its mind. One song morphs into the next before you really notice what’s going on. In Kiki and Herb’s beloved Christmas medleys, “We Wish You a Merry Christmas” becomes the Velvet Underground’s “Heroin”; “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” becomes Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” The tour de force in the current show begins with “Whitey’s on the Moon,” Gil Scott-Heron’s protest song about moon landings and racial injustice. After a minute or two, Scott-Heron’s spoken-word anthem has mutated into latter-day rap—Eminem’s “Lose Yourself,” with its inspiring chorus, “You better lose yourself in the music, the moment / you own it, you better never let it go.” A second later, Kiki shrieks, “And you may ask yourself, ‘What is that beautiful house?,’ ’’ and we are in the middle of the Talking Heads’ “Once in a Lifetime.” The transitions are seamless because Mellman translates all the songs into his own peculiar musical voice, which might be described as John Cage cocktail lounge.

When I asked Mellman about the Eminem medley, he said that he had spent a weekend working on it and that the theme of it was appropriation. Kiki singing Eminem is ridiculous; but no less ridiculous than Eminem, a white kid, mimicking black culture, or the Talking Heads incorporating African beats into their SoHo art rock. Every singer, even Gil Scott-Heron, is pretending in one way or another—putting on drag—and Kiki does the service of bulldozing all the façades of authenticity. There’s something liberating about the way the songs break free of categories and come together in a midnight carnival. The music becomes as androgynous as the performer: it is always changing shape and identity. This is probably why fellow-musicians find Kiki and Herb so riveting. Everyone from Lou Reed to the Pet Shop Boys has attended their shows. Among the rock memorabilia that Bond has accumulated is Edie Sedgwick’s leopard-skin pillbox hat; he wears it while singing Bob Dylan’s “Leopard-Skin Pillbox Hat.”

Bond and Mellman are in the curious position of being celebrities’ celebrities—famous to the famous but little known outside the downtown scene. For years, they have contemplated taking their act out of lounges and into legitimate theatres; with some trepidation, they are now doing it. If they find wider fame, it will be richly deserved, but their longtime fans don’t want them to wander too far from their punk-drag roots, when they scared the daylights out of unsuspecting customers. Once, during a show in San Francisco, Bond went to an open window and began shouting to people on the street outside: “Just don’t get too comfortable out there!” ♦Published in the print edition of the May 19, 2003, issue.

John Cameron Mitchell's Shortbus explores the lives of several emotionally challenged characters as they navigate the comic and tragic intersections between love and sex in and around a modern-day underground salon. A sex therapist who has never had an orgasm, a dominatrix who is unable to connect, a gay couple who are deciding whether to open up their relationship, and the people who weave in and out of their lives, all converge on a weekly gathering called Shortbus: a mad nexus of art, music, politics and polysexual carnality. Set in a post-9/11, Bush-exhausted New York City, Shortbus tells its story with sexual frankness, suggesting new ways to reconcile questions of the mind, pleasures of the flesh and imperatives of the heart.

Shortbus (2006), Extended Trailer.

Shortbus (2006) - In the End performed by Justin Vivian Bond.

KIKI & HERB

Photo: Justin Vivian Bond and Kenny Mellman, 2016 for the New Yorker.

Photos of Kiki & Herb at Joe's Pub by Kevin Yatarola for the New Yorker, 2016.

“Total Eclipse of the Heart” with Kiki and Herb. Video directed by Victoria Leacock, 2006.

3 never before released live tracks.

Recorded in various boîtes across the world in the 2000s. Same as it ever was.

All profits go to Black Visions Collective, a Queer and Trans centering organization whose mission is to organize powerful, connected Black communities and dismantle systems of violence…through building strategic campaigns, investing in Black leadership, and engaging in cultural and narrative organizing.

We have covered the cost of the mechanical licenses for the original songwriters and are donating that.

CLICK HERE TO BUY & SUPPORT →

credits

released June 5, 2020

Justin Vivian Bond and Kenny Mellman are Kiki and Herb

Photo by Liz Liguori

Kiki & Herb: Alive on Broadway, playbill from 2006.

Kenny Mellman, left, as Herb, and Justin Bond as Kiki DuRane, in "Kiki & Herb Alive on Broadway."Credit...Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

-

Kiki & Herb: Alive on Broadway

NYT Critic’s PickBy Ben Brantley

Aug. 16, 2006That’s one gorgeous set of teardrops that the immortal Kiki DuRane is wearing for her mind-popping Broadway debut. Kiki, a molting songbird for all seasons, and Herb, her happily suffering shadow and accompanist, opened last night at the Helen Hayes Theater in “Kiki & Herb: Alive on Broadway,” a hyper-magnified cabaret concert that has the heat and dazzle of great balls of fire.

Actually, since this transcendental lounge act is fond of biblical imagery, make that great swords of fire — or, if you prefer, a burning bush.

But about those teardrops. Whenever Kiki tilts her face upward, toward her key light — and like any self-adoring goddess, she does that a lot — her eyes brim with the most brilliant pools of brine you have ever seen. Well, not to spoil the illusion, but those ain’t tears: they’re rhinestones (or something like), strategically glued just beneath her lower lashes.

It is a tribute to the perverse showbiz genius of Kiki and Herb that once you twig on to this shameless trompe l’oeil, you don’t feel merely amused. Nor do you think that the singer has been trading only in paper-moon emotions, or making fun of those who do, as she croons her whiskey-pickled way through bathetic ballads and angry anthems.

Those artificial tears are a comic grace note, sure, but they are also a totem for feelings of devastating depth and substance. And a performance that should, by rights, be just a night of imitative song and shtick from another pair of happy high-campers from the alternative club scene becomes irresistibly full-bodied art.

Fakery is often more real than reality in the glamorous and tawdry world of theater. I should probably state, for the uninitiated, that the ultrawomanly Kiki is channeled by a man named Justin Bond. Herb is the alter ego of a truly inspired pop musicologist named Kenny Mellman.

And while Kiki and Herb claim to be as old as the hills, Mr. Bond and Mr. Mellman are only in their 40’s and 30’s, respectively. The roadmaps of geriatric lines on their faces have been drawn with the blunt bogusness of children portraying grandparents in a school play. And by the way, Kiki and Herb now say the reason they didn’t die, as they had promised, after their farewell concert at Carnegie Hall in 2004 is that they can’t. The reasons are complicated, but let’s just say they involve their having been present at the birth of Jesus.

Believe it or not, that makes sense. In their decade as one of downtown’s savviest acts, Kiki and Herb have always traded on the reassuring illusion of immortality conferred by deeply stylish cabaret performers of advanced age.

You know, the kind you stumble upon after midnight, improbably drawing oxygen from smoky tunes and smoky rooms in bars found everywhere from the inns Ramada to the hotels Carlyle and Algonquin. When Kiki sings — and her numbers go from Eisenhower-era velvet (“Make Yourself Comfortable”) to punk-era tarpaper (the Cure’s “Let’s Go to Bed”) — she suggests some wondrous hybrid of Marianne Faithfull, Elaine Stritch, Patti Smith and Kitty Carlisle Hart. As with those very different women, the point is never the prettiness of the voice but the history behind it and the passion to endure that vibrates within.

There is also the vibrato (real or metaphoric) of suffering, that public overdose of private pain that made Judy Garland a figure of such religious adoration. The references to Jesus in Kiki’s spiels aren’t inappropriate, since Mr. Bond and Mr. Mellman appreciate the role of the self-lacerating performer who cathartically embodies the anguish of his audience. (“Kiki and Herb Will Die for You” is the title of their last CD, a recording of their Carnegie Hall concert.)

Between songs, Kiki describes her early history with an uncaring mother and abusive father (“I always said if you weren’t molested as a child, you must have been an ugly kid”); her childhood in a Pennsylvania orphanage, where she met Herb, a gay Jewish foundling; the seesaw career of high and low living, institutionalizations and shifting musical fashions; and the death of her little daughter, Coco, which Kiki describes while staring into the murky depths of her glass of Canadian Club.

Famous names are tossed into the swirling mix. Kiki danced in burlesque nightclubs with Maya Angelou; she and Herb were supposed to have performed the theme song for Mel Gibson’s Holocaust series on television until his arrest for drunk driving put an end to the project; world leaders (you can imagine which ones) are gutted, roasted and fried.

This sounds like regulation tacky countercultural standup, laced with the overemotional kitsch that drag queens borrow from old movies, right? That sensibility is certainly evoked by Scott Pask’s set — a bizarre sylvan landscape that suggests Salvador Dalí working in Las Vegas and includes a blasted tree that Kiki perches on to sing (and drink) — and Marc Happel’s Loretta Young-meets-Cher costumes.

But like most of the best artists of their generation, Mr. Bond and Mr. Mellman have tunneled under the ironic distance that seems to have been their birthright to reclaim the passion beneath the pose. The musical stylings of Herb (whose liquidly bobbing head and blissed-out expression suggest that his nervous system is located in the strings of his piano) and the vocals of Kiki are radioactive with an angry sorrow, ecstasy and cosmic fatigue so profound that it turns into cosmic punch-drunkenness. They use the surface of camp as a tool for detonating surfaces. (Bette Midler surprised and seduced audiences with just such a style as a singer at gay clubs 30-some years ago.)

It’s a musical approach that finds a common denominator in songs made famous by artists like Public Enemy (quaintly presented as an example of folk music) and the Scissors Sisters and sentimental narratives like “One Tin Soldier” and Dan Fogelberg’s “Same Old Lang Syne.” And who else would segue from the masochistic power ballad “Total Eclipse of the Heart” into a musical setting of William Butler Yeats’s “Second Coming”?

If the idea of the end of the world keeps creeping into the show, that’s appropriate to these times, isn’t it? But Kiki and Herb have been around long enough to know that the threat of doomsday is old news and that life — dammit all — goes on.

At one point Kiki looks into the audience and wonders who on earth is out there. This is Broadway, after all, the place where tourists come from around the country with their families to be entertained. “Do any of you have a family?” she asks of the crowd and concludes that this must be an audience of foundlings.

Maybe. But remember that the subtitle of the show, which runs only through Sept. 10, is “Alive on Broadway,” not merely “Live.” Though they may disappear when the lights go down, and the makeup comes off, Kiki and Herb onstage are Alive with a capital A, with all the human vitality and fallibility that that implies. This is more than can be said for the synthetically enhanced automatons appearing in most Broadway musicals.KIKI & HERB

Alive on BroadwayCreated and executed by Justin Bond and Kenny Mellman; sets by Scott Pask; lighting by Jeff Croiter; costumes by Marc Happel; sound by Brett Jarvis; general manager, Foster Entertainment; production management, Aurora Productions; production stage manager, Peter Hanson. Presented by David J. Foster, Jared Geller, Ruth Hendel, Jonathan Reinis Inc., Billy Zavelson, Jamie Cesa, Anne Strickland Squadron and Jennifer Manocherian in association with Gary Allen and Melvin Honowitz. At the Helen Hayes Theater, 240 West 44th Street, Manhattan; (212) 239-6200. Through Sept. 10. Running time: 2 hours 20 minutes.

WITH: Justin Bond (Kiki) and Kenny Mellman (Herb).

Kiki and Herb, in 2003. Photo by Ruven Afanador for The New Yorker.

-

It is said of many show-business legends that they lose touch with the ordinary world and become cartoons of their former selves. The opulently dissipated Kiki DuRane—a sixty-something lounge singer who tours ad nauseam with a doleful accompanist named Herb—has gone in the opposite direction; she is a fictional creation who has acquired the grit and the glow of the real. Kiki and Herb are the invention of the writer-performer Justin Bond and the pianist Kenny Mellman, who have long been fixtures at downtown New York venues like Flamingo East, P.S. 122, and Fez. They have refined their act into an Off Broadway show, “Kiki & Herb: Coup de Théâtre,” which recently opened at the Cherry Lane. It is a slashingly funny, psychically unsettling entertainment—part cabaret, part rock and roll, part Victorian melodrama—to which the category of camp does not apply. Camp implies knowingness and detachment; Bond’s Kiki is anarchic and atavistic, in the grip of forces beyond her control. She is almost militant in her decrepitude. Reminiscing airily about her old friend Grace Kelly, barking obscenely at childhood foes, drifting into a sullen stupor, snapping back to life with yawps of vicious glee, Kiki is a beacon of insanity in a world that may finally be coming around to her point of view.

The conceit of the show is that Kiki, a self-described “boozy chanteusie,” is aiming to attract new listeners by singing contemporary hits. “It is both thrilling and humbling that so many young people have, as it were, ‘tuned in to our sound,’ ” she says, with the overenunciation of the early-evening alcoholic. Thus begins a scorched-earth advance across decades of pop music, from Bob Merrill’s “Make Yourself Comfortable” to Kylie Minogue’s “Can’t Get You Out of My Head.” Kiki’s wild stabs at modern trends recall such classic miscalculations as Mae West’s renditions of Beatles songs and Ethel Merman’s disco album, but the genius of Kiki is that her entire career seems to consist of bungled crossover projects: a bossa-nova album (“Kiki and Herb: Don’t Blame It on Kiki and Herb,” 1964); a spoken-word record (“Kiki and Herb: Whitey on the Moon,” 1972); a belated disco effort (“Kiki and Herb: One Last Chance to Blow,” 1983). The songstress hurls herself at this material with such dire enthusiasm that she takes full possession of it. Lately, she has taken an interest in rap, which she calls “the folk music of today.” In past shows, she has sung Wu-Tang Clan and Snoop Doggy Dogg, adding jazz vocalise to such lyrics as “All my niggaz and my bitches / Throw your motherfuckin’ hands in the air!” This time, she takes on Eminem, whose self-pitying hysteria suits her beautifully.

Between the songs come autobiographical vignettes. Bond has mapped out the life of Kiki in loving detail, and each show adds a few new twists to the familiar downward spiral. The singer was born during the Great Depression, overshadowed by tragedy from the start. “A lot of people jumped out of windows when the stock market collapsed in 1929,” she recalls, “but not all of them died. My father was such a man.” She was given the diagnosis of “retard” and placed in a children’s institution in western Pennsylvania. There she met Herb, a foundling of indeterminate origin. When Herb fell victim to a predatory delinquent named Danny, Kiki was there to comfort him, and a great friendship was born. (The Danny episode inspires one of the show’s set pieces, a dramatic monologue built around the song “I’m Ugly and I Don’t Know Why,” by an obscure band called Butt Trumpet, with adornments from the inspirational Christian poem “Footprints.”) The duo’s musical career developed only in fits and starts. There was a prolonged interruption when Kiki had to serve a jail sentence for the attempted murder of her first husband, an abusive boxer named Ruby. “I wasn’t trying to kill him,” Kiki explains, “only trying to get his attention.”

Throughout the evening, the chanteuse looks back wistfully to the year 1967, when her life turned momentarily grand. A flashback sequence re-creates the scene: Kiki and Herb are playing at the Grand Casino, in Monte Carlo, at the invitation of Princess Grace. They are making what should have been their triumphant comeback album, “Kiki and Herb: It’s Not Unusual.” Kiki has Aristotle Onassis as a lover, Maria Callas as a rival. Fortune has raised her up, but now a terrible tragedy lays her low. During a Mediterranean cruise, she leaves her seven-year-old daughter, Coco, alone on deck while she goes below to satisfy her carnal needs. “Ladies and gentlemen,” she says, head cast down, “where the hell can a kid go on the deck of a boat?” At this juncture, the performance begins to waver between black comedy and something like genuine pathos. Kiki’s failures as a singer pale next to her failures as a mother. The watery death of Coco haunts her. She has lost touch with her two other children, who claim not to know her, even though she sends them all her press clippings. She takes refuge in another glass of Canadian Club and ginger ale—the piano is equipped with a drink holder—and the drink begins to take its toll. She digresses, and digresses again—“Where was I, ladeezh n genlmn?”—and then stops, staring fixedly at nothing.

Just when it seems that the comic spirit of the evening has been swallowed up in melancholy, the original, rampaging Kiki returns, her extreme jazz vocals now fuelled by rage at herself and the world. She turns for solace to her fans, who have always stood by her side, albeit in dwindling numbers. What the world needs, she says, is more love, for “without love . . . there is only rape.” “

"Kiki & Herb” is a comedy, at least on the surface, but the performers are serious people who have managed to smuggle into their act a fair degree of theatrical and musical sophistication. Bond, who is forty, is a native of Hagers-town, Maryland. He studied classical acting in London, but he developed a distaste for that aspect of theatre which involved working with directors. He moved to San Francisco in 1988 and threw himself into street theatre, avant-garde noise, and conceptual cabaret. One night, while trying to think of an innovative birthday present for a friend, he drew age marks on his face and assumed the Kiki persona. He is resigned to being labelled a “drag queen,” although, after meeting him offstage, you want to find a mellower label for his particular brand of gender vagueness. Bond is simply a svelte person who looks stylish in women’s clothes, especially swinging-sixties outfits, like the ones that Faye Dunaway wore in “The Thomas Crown Affair.”

-

A blood-curdling scream, accompanied by sleigh bells and blustery winds, is your welcome to the tragicomic holiday world of the now-extinct cabaret duo known as Kiki and Herb. Though they stuck around for what seemed like an eternity—perhaps fifty years, perhaps thousands—time was not their friend. It found Herb, a gay Jew on the spectrum, hammering away endlessly at the piano while a soused Kiki stood in front of it, ruminating on life’s absurdities and venting her rage through the songs of the kids—Nirvana, Kate Bush, Depeche Mode, ABBA. Herb chimed in with Tourette-like shrieks and lobotomized mumbles. Christmas, as this album reveals, only made their problems worse.

Whether or not they are, in fact, dead—they’ve surprised us before—Kiki and Herb remain two of cabaret’s greatest creations. We can thank their alter-egos, Justin Vivian Bond and Kenny Mellman, for unleashing them on us in the early ‘90s. Their unhinged punk-rock intensity and free-falling sense of danger riveted a young audience who had never known how exciting cabaret could be. Every show was a cathartic relief, a laugh riot, and a rallying cry to break out the booze and have a ball, no matter how bleak the future seemed.

At first a cult phenomenon, the act kept growing. Kiki and Herb made it to Carnegie Hall (twice), the Sydney Opera House, and Broadway, where they played a Tony-nominated run. They split in 2008, but reunited eight years later for a 22-show stint at Joe’s Pub in New York. The demand for tickets crashed the club’s server.

Do You Hear What We Hear? was first released in 2000. It vanished as fast as your first Merlot at a family Christmas. The album immortalizes a show that Bond and Mellman performed almost every December of their partnership—from their fledgling days at Eichelberger’s, a club in San Francisco, to 2007, when they brought the program to Carnegie Hall for their second concert there. Now this rarity is back—and it is still a feast for anyone whose heart sinks at the thought of one more season of enforced merriment. “It’s Christmas? Okaaaaayy!” moans a resigned Kiki in her cigarette-scarred foghorn voice. The ten-minute Opening Medley is a frantic encapsulation of how the holidays barrel into our lives, dragging us through a blizzard of frozen smiles and saccharin feelgood tunes. Radiohead’s “Creep” (“I’m a weirdo/What the hell am I doing here?”) and Eurythmics’ “You Have Placed a Chill in My Heart” are dropped in as clues to how Christmas is really affecting us. “Ladies and gentlemen,” admits Kiki, “sometimes I feel just like Mary’s donkey. Every finger in the room is pointing at me.” In her slurred autobiographical monologues, every betrayed yuletide dream is dragged out of storage and hung up with the stockings.

The team’s visuals—Kabuki-like facial lines etched in black; Herb’s docile, vacant stare versus the crazed wildcat eyes that would suddenly pop out of Kiki—were a big part of the fun. So was the audience, who egged them on to new heights of pandemonium. It fell to the album’s producer Julian Fleisher—a much-respected singer-songwriter, host, and director on the downtown New York scene—to translate a live experience into sound. What he achieved is as vivid as the best of radio’s golden age. The theramin-like instrument heard in the “What Child Is This?” medley is a saw, played here by its owner, a homeless man whom Fleisher had heard on the street. Its ghostly, off-key wobble helps de-sanctify the birth of Baby Jesus. (The virginal tones at the end come from Debbie Harry.) An all-star chorus (see credits), singing in messy unison, puts us in a pub at last call for “Those Were the Days,” a drunken toast to lost innocence. Mellman has a sweeping grasp of pop styles across time, and he can shift gears in a heartbeat. But we rarely heard him sing a solo as Herb. Fleisher had him do one here on Suede’s “The Big Time,” a song about how fast the spotlight can flicker out, if it ever shines at all. To hear the inner Herb slither out is hair-raising.

Mellman and Bond are clearly not afraid of the dark. Radiohead’s somber “Exit Music (for a Film)” could be the soundtrack for a tiptoed escape from the family house before dawn breaks on Christmas. Marianne Faithfull’s “Times Square,” cowritten with her guitarist Barry Reynolds, goes from chilling to apocalyptic as we envision crowds of holiday shoppers and LED screens showing Santa. “Take a walk around Times Square,” Kiki yowls, “with a pistol in my suitcase and my eye on the TV.”

Amid the chaos is a sweet song by Melanie, “Tonight’s the Kind of Night.” It taps into the pathos that made Kiki and Herb so ultimately touching. Suddenly the decades melt away, and we hear two wounded children, wishing that their Christmas fantasies might actually turn out to be true. ― James Gavin

Running Up That Hill also available on Spotify and Apple Music.

Frosty the Snowman also available on Spotify.

May 1999 Mx Justin Vivian Bond and Kenny Mellman at Flamingo East.

Kiki and Herb, 1993. Flier by Daniel Nicoletta.